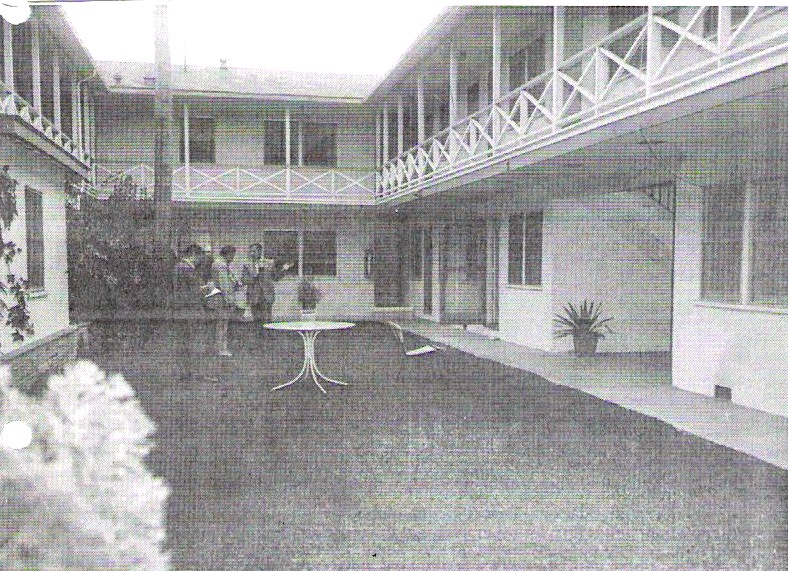

Linda Cummings first day at unit #8 in The Aladdin Apartments was anything but magical. She was drugged, raped and strangled.

Her killer then tightened a rope around her neck and hung her naked body two feet off the floor of her new apartment in a pathetic attempt to make it look like a suicide. And then he told preposterous lies that Linda had no friends, no family and had just been released from a mental stay at a local hospital.

But it worked.

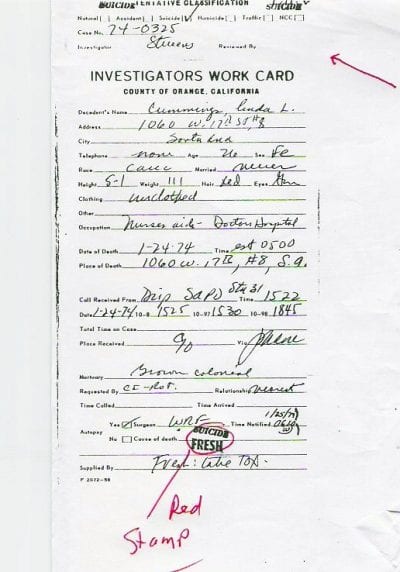

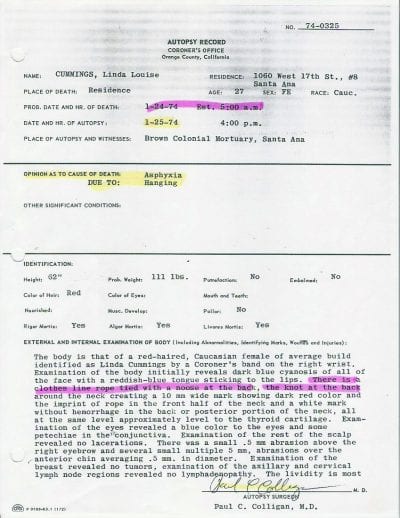

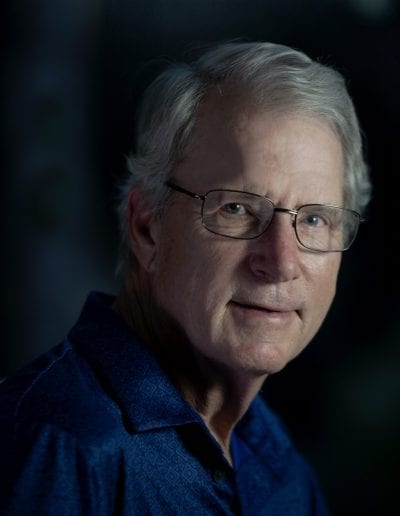

A deputy coroner prematurely, mistakenly and incredibly red-stamped cause of death as SUICIDE.

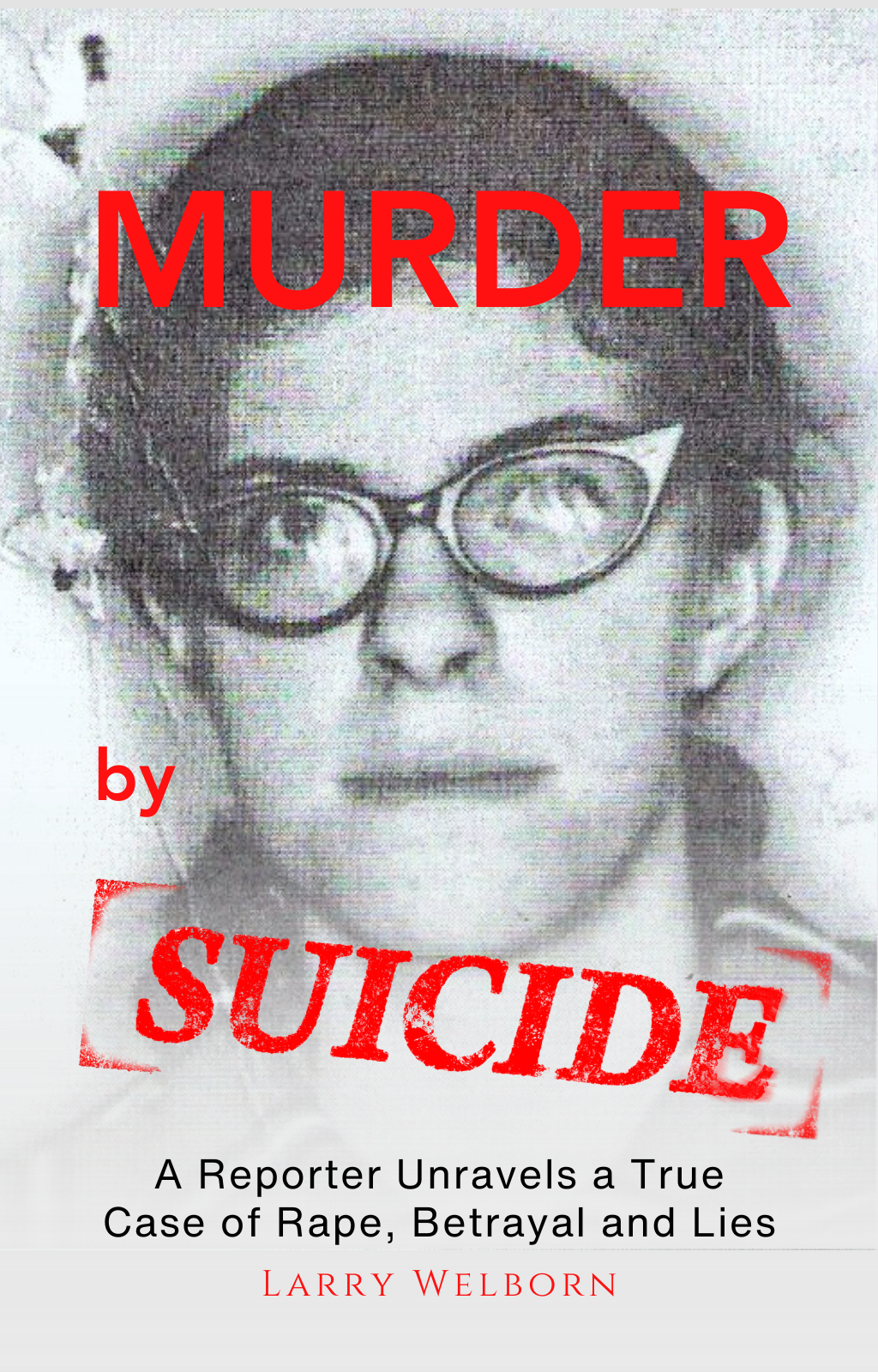

It wasn't long before most folks at The Aladdin forgot the tragic story about the young woman with the pointy glasses who killed herself in apartment 8.

But then another woman was strangled in an apartment at The Aladdin.

The killer may have confused the cops, fooled the coroner, and beat the system, but he didn’t factor in one thing: a tenacious newspaper reporter who refused to believe Linda Cummings killed herself.

What follows is an extraordinary tale of diligence over the span of a lifetime by journalist Larry Welborn to expose the truth of a murder camouflaged to look like a suicide.

This is not your typical detective whodunit mystery.

This is a story demonstrating to what lengths a journalist will go to stand up for an underdog.

This is the true story of Welborn’s 46-year quest to find redemption for a young woman who was determined to live a happy life in 1974.

His stubborn pursuit of the truth – and of Linda’s killer – is the heart of this book. The tale spans decades of his journalism career.

Sometimes it reads like a modern version of Les Misérables, where justice and the good guys were the real victims and where lies, pretense, and deceit too often prevailed.

But Welborn pestered the police, challenged prosecutors and pushed Linda’s injustice up the hill over and over for nearly a half-century until he found a small measure of justice.

He not only shows how and who killed Linda Cummings, he also confirms that she was a spunky young woman, beloved by many, and still deserving of some kind of justice a half-century after her death.

In the end, it is one journalist’s dogged pursuit of the truth that ultimately makes this true crime story a triumph for her loved ones – and for those who care about getting the story right.

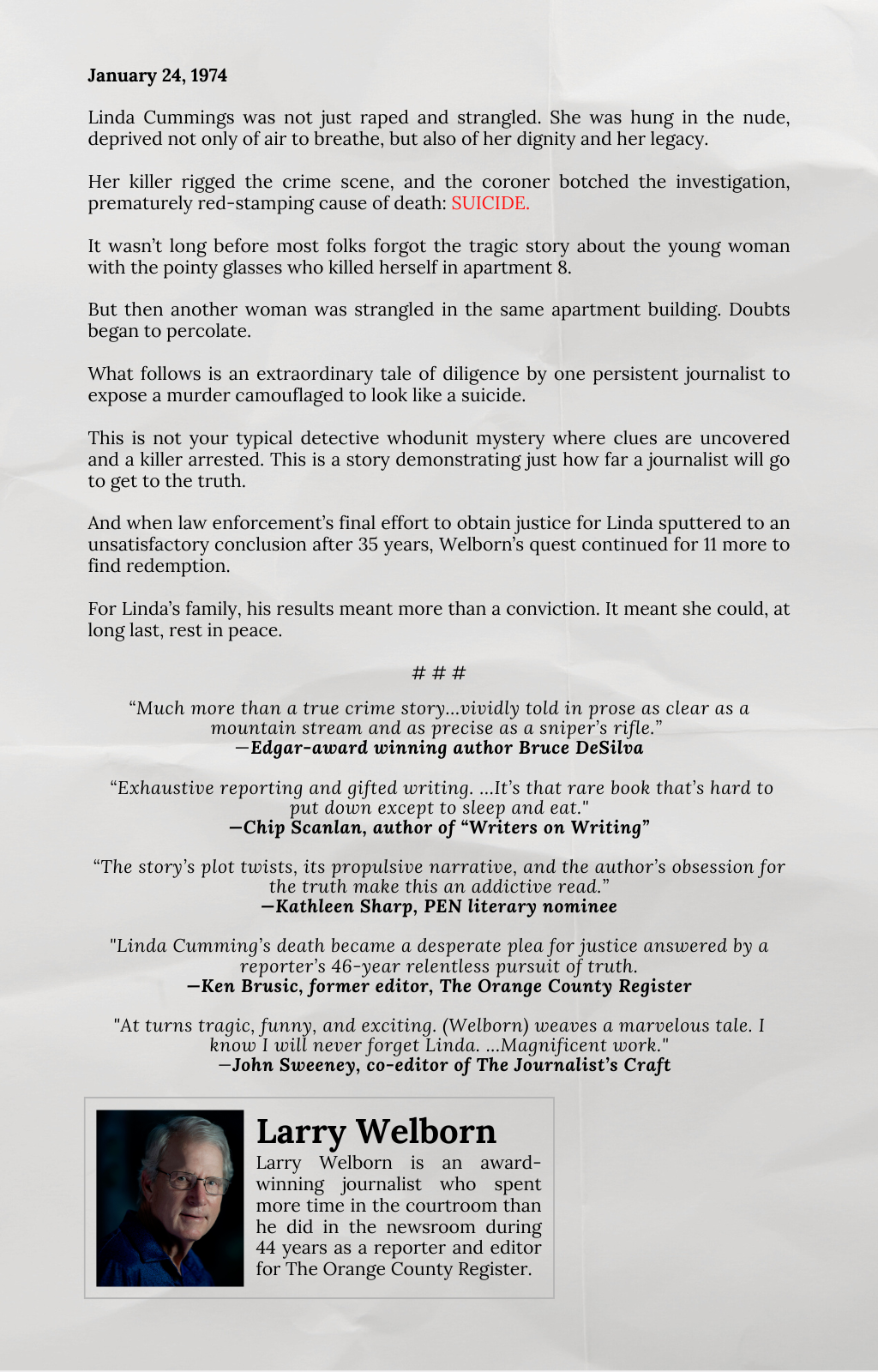

Larry Welborn

Larry Welborn is an award-winning journalist who spent more time in the courtroom than he did in the newsroom during his 44 years as a reporter and editor for The Orange County Register. He covered more than 500 trials in his career, starting with the Charlie Manson case in Los Angeles, and ending with the trial of two Fullerton Cops who beat a homeless man to death. He even covered the murder trial of a close friend and fellow journalist who drank too much cheap wine and stabbed his wife 47 times. Welborn once researched, compiled and wrote “The Notorious OC,” about the 60 most newsworthy cases in county history, compelling an appellate court justice to dub him “The Dean of Courthouse Reporters.” A pimp on trial for killing his best prostitute because she was too tired to turn one more trick so he could buy a lid of grass once threatened Welborn for “writing shit about me.” Welborn has interviewed several men on death row, and once engaged in a three minutes and 15 second staring contest with a serial killer. But of all those cases, the one that jolts his brain when he is jarred awake in a cold sweat by a nightmare that never ends is the unheralded death of Linda Cummings.

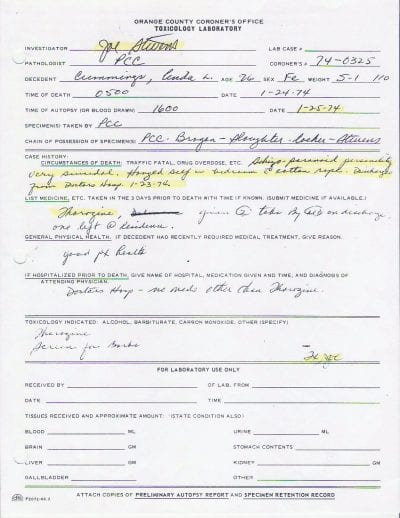

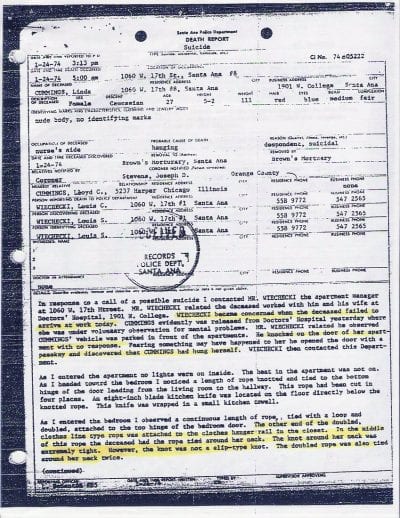

Documents

In my 46-year quest seeking justice for Linda, I copied and saved thousands of pages of public records, police reports, legal filings, letters, notes and photographs. I reviewed old newspapers on microfiche and read hundreds of pages of transcripts, dating from the 1960s and into the 2010s. I collected binders full of information and images I hoped would someday help me write a compelling story about a young woman who had been victimized by others with more clout, power and strength.

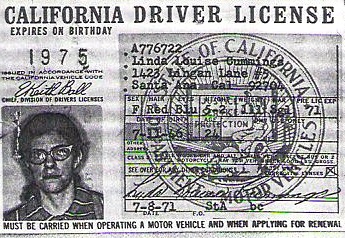

Linda Cummings

She was two years older than I when she died on Jan. 24, 1974, inside Apartment 8. Her age became frozen in death -- forever 27 -- same as Jim Morrison and Amy Winehouse. But as I continued my journalism career, my age never stopped advancing 27, 35 … and beyond. Somewhat to my surprise, I became Linda’s surrogate big brother -- the kind of big brother who would stand up for her – the same way a newspaper stands up for the underdog.

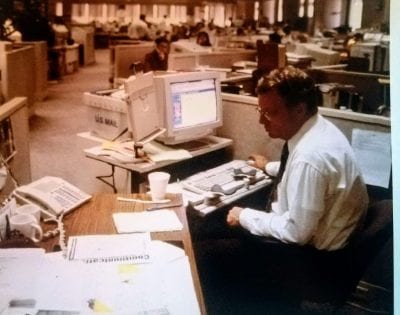

The Journalist

In October of 1974, I received a phone call at my desk in the courthouse pressroom from a woman who saw my byline in The Orange County Register. She was crying when she told me what happened to Linda Cummings.

That story has been ringing around in my head ever since.

They found her in the nude with a rope around her neck in unit # 8 at The Aladdin apartments in Santa Ana. Her death was quickly brushed off as a suicide, and when the cops could not immediately find her next of kin, she was buried in inexpensive wooden casket in an unmarked grave. Linda was dead and forgotten -- well, almost forgotten -- and it seemed no one cared. Evil had won.

But sometimes, a small act of decency can alter that scenario and one phone call can make a difference.

I’ve been looking into the odd circumstances surrounding Linda’s death since I answered that phone. I discovered evidence that convinced me Linda had been raped and strangled and hung in the nude, deprived not only of air to breath but also of her dignity.

After 44 years, could I prove it?

###

I think I was always meant to tell this story.

It started in 1962 when I decided I wanted to become a journalist and cover major league baseball. I made that decision after I read “Freshman Backstop,” a young adult book by Lawrence A. Keating, about a short, no-power, college freshman baseball player, who also wrote for the college newspaper.

Actually, what I really wanted to become was a baseball player, but I wasn’t as athletic as Shorty, the protagonist freshman catcher.

But I bet I could write better than Shorty.

I took "Beginning Journalism" as a freshman, wrote feature stories as a sophomore, became sports editor as a junior, and then editor-in-chief as a senior of my high school newspaper El Rodeo, at El Rancho High School in Pico Rivera.

My big break came after my junior year in high school when I applied for and was accepted to a learn-by-doing sports writing workshop at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, founded by the legendary Los Angeles Examiner sports writer Ralph Alexander.

While I wasn’t the best writer in that California Scholastic Press Association workshop (we also had Los Angeles Times reporter and best-selling author William C. Rempel; future San Francisco Examiner Executive Editor Narda Zacchino, and future Life Magazine photographer Sergio Ortiz), I was one of the most determined.

Alexander, who covered the 1960 Rome Olympics, met Eleanor Roosevelt and guided the CSPA Workshop for 31 years, took me under his wing. He was a curmudgeonly gentleman who wore short sleeve shirts, under the same red checkerboard sports coat for years. He once was called “Old Asbestos Lips” because he smoked one cigarette after another as he typed (by the hunt and peck method) until he quit one-day cold turkey – because he didn’t want to be a bad role model for the kids at the workshop. He helped hundreds of young journalists get their start in this wonderful business. I was one of them.

First, he helped me get a scholarship to Pepperdine College in Los Angeles, where I became editor of “The Graphic” newspaper, elected First Vice President of the California Intercollegiate Press Association, and named to “Who’s Who in American Colleges and Universities,” and from which I graduated in three-and-a-half years.

Second, Ralph got me a two-week gig as a stringer for “Der Spiegel,” the German news magazine, covering the Manson Family murder trial at the Criminal Courts Building in Los Angeles.

At the time, The Manson murder trial was hailed by some as “The Trial of the Century.” Legendary Hearst reporter Adela Rogers St. John, however, insisted that the Bruno Hauptmann trial in the Lindbergh baby kidnapping was even bigger.

Anyway, there I was, sitting in the courtroom gallery for two weeks with Linda Deutsch of the Associated Press and dozens of other top journalists -- until the regular Der Spiegel reporter arrived and took my spot. I was definitely out of my league.

And third, Ralph helped me get my first full-time journalism job at what was then called the Santa Ana Register in 1970. It was the fastest growing newspaper in the United States for a while. It changed its name to The Orange County Register and it won three Pulitzer Prizes during my tenure.

I included on my resume for that job that I attended the CSPA workshop, had a part-time job replacing the pocket parts in my Dad’s law books every year, and that I covered The Manson trial. I actually read some of the cases in the new pocket inserts, and understood how they worked. When a scandal erupted over the county supervisor’s voting themselves a huge pay raise, I managed to find a new law in one of those pocket inserts that lead to a Register exclusive by Larry Welborn.

When in January 1974, the junior courts beat opened up at The Register, the editors thought of me, apparently believing I had some legal acumen.

Over the course of my 44 years at The Register, I covered the courthouse beat three separate multi-year stints. I was the courts and cops editor for another term.

For 12 years, I was the paper’s training editor who organized the National Writers’ Workshop, bringing in top journalists from around the country to talk shop. Linda Deutsch, who is the biggest Elvis fan on Earth, was a featured speaker, as was true crime book author Caitlin Rother, and my friend Chip Scanlan, the head of the writing program at The Poynter Institute for Media Studies.

Even when I was away from the courthouse bureau, I kept track of the comings and goings among lawyers, judges, clerks and bailiffs, often getting tips from old sources that lead to exclusives in the Register.

When the editors sent me back for my third stint as courts reporter in 2002, after my three kids all graduated from college, my business card read Larry Welborn, Legal Affairs Writer, and some judges started calling me “The Dean” of OC courts reporters.

Totaled up, I spent 25 years in a dingy bureau covering hundreds of murder trials, scores of death penalty verdicts, a handful of corruption indictments, including one where Orange County Sheriff Michael Carona was convicted and sentenced to federal prison for six years. I once had a 3 minute 15 seconds staring contest with a serial killer. A pimp on trial for stabbing to death his prostitute wife because she was too tired to turn one more trick once threatened me in court for “writing shit about me.” A close friend and fellow journalist once asked me to cover his trial after he stabbed his wife to death after drinking a bucket full of cheap wine.

I’ve cultivated as sources judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, clerks and bailiffs. I interviewed serial killers, cop killers, and cops who’ve killed. I had a front-row seat in the courtroom gallery to some of the most gruesome cases in Orange County history.

It was the best of times for an ink-in-the-blood newspaperman. I strongly believed that we as journalists have the responsibility to:

-

Stand up for underdogs by telling their stories

-

Reveal the truth wherever it takes us

-

Make people care by writing powerful stories about compelling things.

-

Hold people in power accountable

-

Make a difference

During one of my first assignments as the criminal courts reporter for The Orange County Register I became aware of the Linda Louise Cummings story.

Her childhood had been heartbreaking and tragic. She struggled as an adult, was always the underdog, and never got any breaks.

Her mysterious death on Jan. 24, 1974 was not a suicide. I believe she was raped, strangled and hung by her neck by an evil force inside Apartment 8 at The Aladdin apartments.

And when she was buried in an unmarked grave in an inexpensive wooden casket, it seemed like nobody cared.

Well, maybe somebody.

Linda Cummings

Somebody Cared

I never met Linda Louise Cummings.

Our paths did not cross until after she was dead, buried and forgotten.

But in decades of researching, investigating and writing about the circumstances of her troubled life and mysterious death, I came to admire her courage and appreciate her toughness.

She was two years older than I when she died on Jan. 24, 1974, inside her apartment in Santa Ana, California. Her age became frozen in death -- forever 27 -- same as Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin and Amy Winehouse. But as I continued my journalism career, my age never stopped growing, 27, 35, even 50 … and beyond.

Somewhat to my surprise, over time, I became Linda’s surrogate big brother -- the kind of big brother who would stand up for her – the same way a newspaper stands up for the underdog.

After I first heard about the sad, shocking and tragic sequence of events that put Linda in harm’s way, I spent 44 years – and counting --patching together a quilt of her life, piece by piece, stitch by stitch.

In 1974, I reported and wrote an exclusive story in the Santa Ana Register about how her nude body was discovered hanging by a clothesline with a non-slip knot tied behind her neck and then stretched oddly between a closet rod and a door hinge.

The deputy coroner ruled it was a suicide. I knew it was murder.

I didn’t write her name in print again for 31 years, while a penetrating image from her drivers’ license continued to pop into my subconscious mind. The unsmiling face with cat’s eye glasses urged me to do something to restore her dignity, to make people care, to seek justice.

I interviewed hundreds of people, including her stepmother, stepsister, half-brother, cousins and friends…the few I could find. I talked with scores of cops, prosecutors, defense attorneys, clerks and judges. I challenged authorities to look closer at the circumstances of her death. I pressed more than one deputy district attorney about why no one was charged in connection with her death.

I copied and saved thousands of pages of public records, police reports, court documents, notes and photographs. I reviewed dozens of pages of old newspapers or photographs. I read hundreds of pages of transcripts, dating from the 1960s and into the 2010s. I collected binders full of information and images that I felt would someday help me write a compelling story and find justice for a young woman who had been victimized by others with more clout, power and strength.

I traveled to Northern California, Wisconsin, Florida and Nevada collecting information.

I interviewed two of the four people who played significant roles in the sequence of interactions on Linda’s final night on earth. Those interviews spliced together with police reports, court testimony and photographs helped me piece together a moment-by-moment recreation of most of the damning things that happened inside Apartment 8.

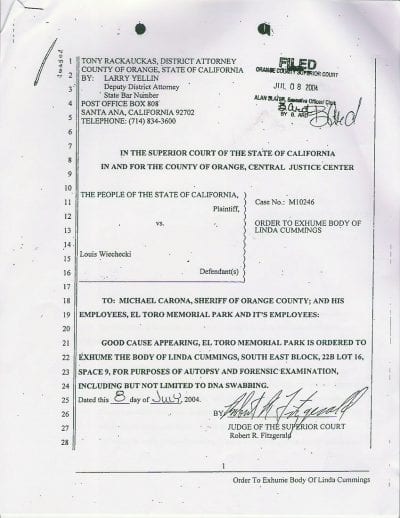

In 2005, my efforts for the now Orange County Register led to a S.W.A.T. team arrest of a fire-starting, cat-killing ex-convict with a MENSA IQ on a single felony charge: the murder of Linda Louise Cummings.

But in 2009, an Orange County judge dismissed the case because of “extreme, prejudicial and unjustified delay by the passage of time … caused destruction of evidence, the loss of records, the failure of memories and the death of witnesses.”

The killer’s attorney argued that the “case at bar” was not from any initiative by the District Attorney’s Office, not by any advance in the state of art of scientific criminal investigation, and not by further discovery of anything of evidentiary value, but instead by “the fortuitous and extrinsic circumstance of goading by newspaper reporter Larry Welborn of the Orange County Register who was seeking to weave the tapestry of an engaging human interest story on the putative fate of Linda Cummings.”

I had pushed Linda’s boulder to the top of the hill too many times seeking to show that her life mattered and that people cared. But I had failed.

Linda Cummings’ remains were placed in a new casket and reburied in a crowded public cemetery in El Toro.

I retired from the newspaper game after 44 rewarding years of investigating, researching and writing stories that mattered by using tools and techniques passed on to me by editors, teachers, mentors and colleagues.

But I left one story unfinished that was eating a hole in my soul; that haunting image of the saddened woman in the cat’s eye glasses would not let me retire until I told her complete story.

Linda Louise Cummings was a troubled, shy and withdrawn young woman who endured heart-wrenching emotional hardships at an early age, and then challenged them head-on as a kind and caring adult just before she was killed.

She was a combatant with fierce determination who was also fragile, naïve and alone. And she was on the cusp of success, happiness and normalcy, just before she was murdered.

What happened to her shouldn’t have happened.

In 2018, a reader in Albany, New York, sent me dozens of journals, papers and research by one of Linda Cummings’ deceased brothers written decades ago that revealed parts of their family history in foster care and a heartbreaking story of abandonment. I received a letter written by her older sister that documented tragic events that shaped their lives. I accessed never-before-seen police records from The Orange County District Attorney’s Office that provided brighter illumination on what happened on the night Linda died.

As a journalist, I continued to learn everything I could about who Linda Cummings was, how she died and why she died to provide texture, meaning and definition to her short, difficult and anonymous life.

I want people to know and understand one unchallengeable, unquestionable true fact: somebody cared.

--Larry Welborn

Blurbs

"Murder by Suicide; Unraveling a Case of Rape, Betrayal and Lies, is much more than a true crime story. It is a story about one reporter’s undying dedication to the truth. After a botched investigation into a suspicious death resulted in a suicide finding, journalist Larry Welborn couldn’t let it go. He kept digging – and pushing several generations of law enforcement officials to join him in the effort – for FORTY SIX YEARS until they provided the victim’s family with a small measure of solace. The tale is vividly told in prose as clear as a mountain stream and as precise as a sniper’s rifle.”

--Bruce DeSilva,

Journalist, writing coach, author

Edgar Award-winning author of the Mulligan crime novels.

"Larry Welborn’s intense debut Murder by Suicide; Unraveling a Case of Rape, Betrayal and Lies, is part true-crime suspense, part newsman memoir, and wholly successful. The story’s plot twists, its propulsive narrative, and the author’s obsession for the truth make this an addictive read. Welborn is that rare breed of criminal justice warrior and evocative storyteller—just what we need right now."

--Kathleen Sharp

PEN Literary Journalist nominee,

Author of Blood Feud: Blowing the Whistle on One of the Deadliest Pharmaceuticals Ever (Dutton)

"For forty years, journalist Larry Welborn pursued the case of Linda Cummings, a young woman on the cusp of a new life who was found dead in her Southern California apartment in 1974. Welborn’s digging finally got the attention of law enforcement and his book tells the story of a remarkable crusade for justice. Exhaustive reporting and gifted writing make Murder by Suicide; Unraveling a Case of Rape, Betrayal and Lies, a must-read for fans of true crime. It’s that rare book that’s hard to put down except to sleep and eat."

--Chip Scanlan, journalist, author

Former writing program director, The Poynter Institute

Author of Writers on Writing: Inside the lives of 55 distinguished writers and editors. (Amazon)

"Linda Cumming’s death became a desperate plea for justice answered by a reporter’s 46-year relentless pursuit of truth. She would have been forgotten, but (Welborn) never stopped digging -- and believing."

--Ken Brusic, former editor, The Orange County Register

"An incredibly good read, at turns tragic, funny, and exciting. (Welborn) weaves a marvelous tale. I know I will never forget Linda. ...Magnificent work."

--John Sweeney, co-editor of The Journalist’s Craft

Images